Processed Foods: Business First vs. Health First—It Depends on Your Seat at the Table

From day one, food corporations have known they couldn’t compete with freshly cooked meals made locally—too slow, too seasonal, too expensive. So they sold us something even more potent: the idea that convenience is king, and nutritious-ish processed products are the loyal subjects we’ve been waiting for. Turns out, we loved the narrative.

Aisles That Never Sleep

Fast-forward to today: ultra-processed foods dominate supermarket shelves. One study using AI to score over 50,000 products across Target, Walmart, and Whole Foods revealed that ultra-processed items make up around 70–73% of the U.S. food supply. Even more telling: minimally processed foods occupy only a sliver of shelf space. And here’s the clincher—every 10% increase in processing score corresponds to about 8.7% lower price per calorie. Budget-wise, that’s a tempting whisper: “Why pay more for real food?”

When Dollars Tighten, Health Slides

In Australia, with the cost of living biting hard, families are cutting down on fresh produce and leaning into cheaper, less healthy options like snacks and confectionery. This isn’t just coincidence—it’s the calculated payoff of decades of marketing pitched on our busiest, most tired selves.

Money Talks, Ingredients Walk

Companies are in it to win it—for their shareholders, not your pancreas. Clean labels, added nutrients, “mmm‑microwave magic” all serve one purpose: make processed food feel like real food—without eating into their margins.

The Nova classification highlights it starkly: ultra-processed foods are engineered for profit, with cheap ingredients, extended shelf-life, branding for days—and they conveniently leave nutrients, transparency, and actual health on the cutting room floor.

How Much of Our Diet Is Ultra-Processed?

It’s easy to forget just how much shelf space and stomach space ultra-processed foods now occupy. Here’s what the research says about the share of daily dietary energy coming from UPFs across different countries: Some are definitely doing better than others but all are on the rise.

- United States – 58% of daily energy from UPFs (NHANES data; Harvard analysis).

- United Kingdom – 50% (Cambridge Public Health Nutrition, household data).

- Germany – 46% (Cambridge, household data).

- Sweden – ~44% (EuroHealthNet policy précis).

- Australia – 42% (BMJ umbrella review, 2023).

- Japan – 38% (Saitama study, Public Health Nutrition).

- Southern China (Guangdong) – rose from 0.9% to 8.5% between 2002 and 2022 (MDPI, 2023).

- Portugal – 10% (Cambridge, household data).

- Italy – 13–14% (Cambridge & EuroHealthNet).

- Romania – 14% (EuroHealthNet).

Why it Matters

- Higher UPF intake is consistently linked to greater risks of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancers, mental health disorders, and premature mortality (BMJ, The Lancet, Systematic Reviews Journal).

- The contrast is striking: a Portuguese diet with only 10% UPFs vs. an American diet with nearly 60%. That’s not just cultural preference—it’s marketing, economics, and policy at work.

…But Why is it so?

“By now you may be wondering—if all this is readily available information, and the health risks are written in black and white—why are we still treading this path? The short answer: business is booming. Corporate lobbying keeps regulations light, governments rely on the jobs and tax revenue these industries provide, and the food system has become entangled with advertising, packaging, transport, and agriculture. In short political cycles and the convenient myth of ‘personal responsibility,’ have made it easier for policymakers to look the other way while companies keep selling convenience. The result? Our long-term health becomes collateral damage in a game where profits win the first move.

1. The Lobby Elephant in the Room

Big Food spends serious money to make sure their products stay in prime supermarket real estate. Lobby groups like the Australian Food and Grocery Council, American Beverage Association, and equivalents across Europe maintain strong relationships with policymakers. They argue regulation will hurt “consumer choice” and the economy—language politicians find safer than telling voters to eat fewer chips.

2. Tax Revenues and Political Appetite

Governments profit from the very products they claim to discourage:

- GST/VAT on processed foods = billions in easy tax revenue.

- Companies employ huge numbers of people, meaning jobs, payroll tax, and exports.

So there’s a perverse incentive: too much regulation might shrink a revenue stream they’ve come to rely on.

3. The “Personal Responsibility” Narrative

It’s politically convenient to frame poor diets as individual choice, not systemic failure. This dodges responsibility for regulation and allows governments to say: “We gave people the guidelines, if they want to eat burgers, that’s on them.”Meanwhile, the industry spends billions ensuring burgers are the easiest choice in the room.

4. Employment & Industry Chains

Processed foods aren’t just manufacturers. They keep entire ecosystems ticking:

- Advertising agencies

- Packaging companies

- Trucking and logistics

- Agribusiness producing corn, soy, palm oil

- Retailers relying on cheap, shelf-stable stock for margins

If you tighten the tap on UPFs, you shake multiple industries. Governments fear being blamed for lost jobs and rising prices.

5. Short-Term Politics vs. Long-Term Health

Health benefits from reduced UPF intake are long-term—fewer cancers, lower healthcare costs, better productivity decades down the line. Politicians work on short election cycles, where immediate wins (jobs, GDP, cheap groceries) beat long-term prevention. Regulating UPFs doesn’t deliver a ribbon-cutting photo op.

6. Fear of Corporate Muscle

Think tobacco wars, but with even broader industry entanglements. Food corporations are bigger, more diverse, and often tied into agriculture, supermarkets, and global supply chains. The fear of legal battles, lobbying blowback, and “nanny state” accusations keeps most governments timid.

The Catch in a Nutshell

It’s not laziness. It’s a cocktail of:

- Corporate lobbying power (loud, well-funded voices)

- Economic entanglement (jobs, tax revenue, supply chains)

- Short-term political cycles (no votes in prevention)

- Convenient narratives (“it’s your choice, not our regulation”)

👉 This is why the rare policies that do get through—like Mexico’s sugary drinks tax, Chile’s warning labels, or UK’s junk food ad restrictions—are so important. They show it is possible, but only when public pressure outweighs corporate pressure.

We Need to Be Our Own Food Detectives

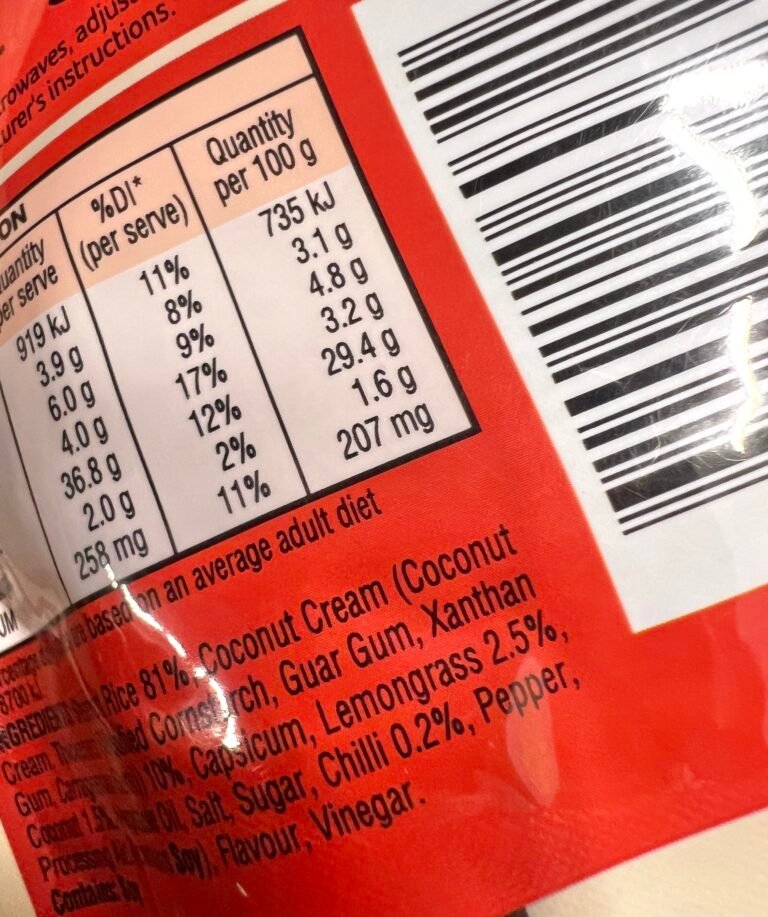

- Mind the processing gap – longer ingredient lists? More colors? Higher price gaps? That’s a clue the product is engineered, not harvested.

- Demand transparency – Nielsen, AI tools like the FPro score (TrueFood.tech), and platform labels are getting smarter at peeling back marketing layers.

- Vote with your trolley – every dollar spent is a vote for what supermarkets stock. Shunning highly processed goods nudges them toward better choices.

- Treat freshness as leverage – make local, seasonal, minimally processed the default—your body (and budget) will thank you.

“Processed foods are not villains in themselves—they are products of a system designed to prioritise profit, scale, and convenience. But the marketing that surrounds them often blurs the line between nourishment and salesmanship. The facts are clear: diets dominated by ultra-processed foods carry significant long-term health costs, while fresh, minimally processed options remain the foundation of wellbeing. It falls to us, as consumers, to recognise that businesses will always act in their own interest—and to make choices that act in ours. By staying marketing-aware and putting health first, we can shift the balance from convenience at any cost to a future where good food and good health sit at the same table.”